Depowering Risk: Vehicle Power Restrictions and Teens’ Driving Accidents in Italy

Balia S., Brau R., Nieddu M.G., 2023 – Journal of Law and Economics

Road accidents are the leading cause of death, especially among young people and teenagers. Therefore, reducing the number of accidents has long been a priority in global political agendas. However, it is a challenging goal to achieve for two main reasons: first, young drivers, in addition to being the most inexperienced, are also more prone to risky driving behaviours such as drunk driving and speeding; second, traditional road safety measures have limited effectiveness, with short-term effects. Such measures as imposing stricter speed limits or tightening penalties for using the phone while driving maintain their effectiveness only in the presence of continuous monitoring and control efforts and often fail to prevent dangerous driving behaviours, only limiting themselves to sanctioning them afterwards. Moreover, when imposed on the entire population, these measures involve high social costs with a very limited return in terms of road safety. Since drivers are heterogeneous in terms of riskiness, tightening measures for everyone – and therefore also for most safe drivers – has a limited impact on road accidents.

However, there is a family of policies that target driver categories to whom a higher risk is attributed a priori: these are the Graduate Driver Licensing (GDL) programs, widespread especially in the United States and Australia. GDLs define a process for obtaining a driving license that, in the first months and years of driving, implies restrictions – such as the interdiction to drive at night or in the company of other underage passengers – that are progressively removed as the driver gains experience. The effectiveness of this type of policy is confirmed by a series of studies, which, however, point out that the outcome depends on a discouragement effect (or incapacitation) rather than a direct effect. In other words, GDLs discourage young people from obtaining a license, which mechanically leads to fewer accidents.

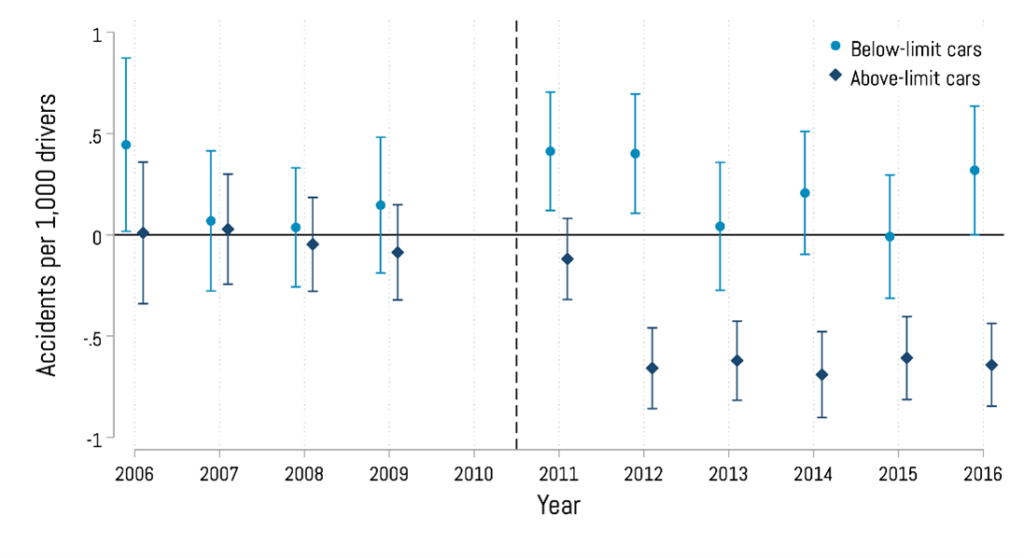

In a recent article, “Depowering Risk: Vehicle Power Restrictions and Teens’ Driving Accidents in Italy”, published in the Journal of Law and Economics, Silvia Balia, Rinaldo Brau and Marco Giovanni Nieddu examine the effects of a reform of Italian traffic legislation, introduced in Italy in February 2011, which is conceptually like GDLs. It indeed establishes that new drivers cannot drive vehicles with an engine power exceeding 70 kilowatts (about 95 horsepower) during the first 12 months of the license. To study the effects of this reform, the authors combine administrative data on all road accidents that occurred in Italy in the decade 2006-2016 with the census of driving licenses. The identification strategy is based on the fact that different cohorts of potential drivers are asymmetrically exposed to the reform. Only those who would have driven vehicles above the limit should be interested in the new regulation. In this way, it is possible to isolate the impact of the introduction of the power limit from that of other policies introduced in the same years. The results show that the limit on engine power reduces the probability of causing a road accident by almost 20% (from 4.4 to 3.6 accidents per 1,000 people). Part of this reduction is due to a smaller number of new drivers, as the number of licenses issued is reduced by 19%. However, the reform has also a direct effect (-13%) on the probability of causing an accident for those who decide to obtain a license despite the introduction of the limit. These results are illustrated in Figure 1, which also shows how the effect of the reform on road accidents can only be observed among vehicles that exceed the maximum allowed power, i.e. those that, from 2011, can no longer be driven by young people. It is important to note that, breaking down road accidents by cause and type, the reduction in accidents among young people is primarily due to a smaller number of accidents caused by speeding. This result seems to suggest that, in the short term, the reform is effective precisely because it prevents risky behaviours – such as reckless driving and speeding – for which more powerful vehicles represent, to a vast extent, a “complementary good”.

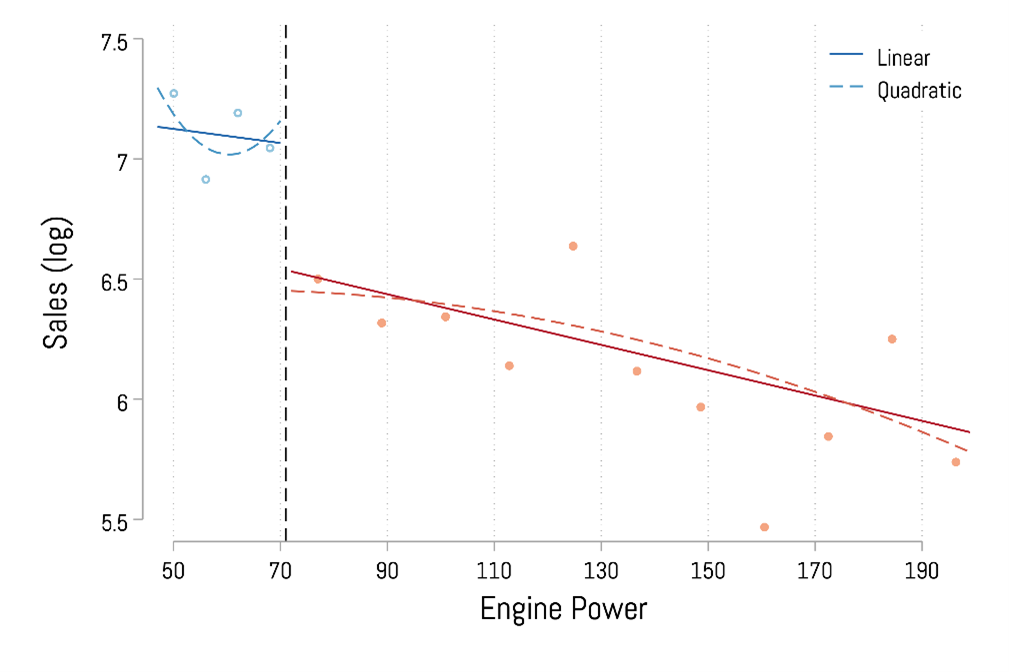

Moreover, the reform also has evident effects in the medium and long term: those who obtained a license in the new regime are less prone to cause a car accident even after the period of restrictions has ended. For this result, the authors suggest an explanation linked to the fact that the rules on the permitted power of vehicles have influenced the choices of car purchases, pushing new drivers – and their families – to opt for cars with lower power. Actually, the data on Italian car sales over the period 2006 – 2016, which are provided by ACI (Automobile Club of Italy), show an increase in sales of car models below the limit, potentially at the expense of models with larger engines. Figure 2 shows that the registrations of car models whose engine is just above the engine power threshold of 70 kW are much fewer – and discontinuously – compared to those with an engine that respects the regulation. This implies that drivers continue to drive a less powerful car, hence less exposed to accident risk, even after the end of the restriction period.

Overall, the results suggest that a feasible and effective strategy to improve road safety is to discourage the occurrence of potentially risky circumstances for younger drivers, such as the possibility of driving high-performance vehicles. In turn, this has important implications in terms of the optimal design of road safety policies. First, these measures do not require constant control by the police aimed at directly preventing (and sanctioning) risky behaviours such as speeding at the exact moment they occur. Secondly, unlike more penalizing measures, like raising the minimum age for obtaining a license, focusing on vehicle power still allows young people to drive, albeit within certain limits. However, as indicated by the results of this study, the success of this type of policy depends finely on their designers’ ability to identify the target population, the principal risk factors and the circumstances to limit, discourage or prevent. In the case of the Italian reform, its success depended precisely on the fact that the circumstance it is meant to prevent – driving high-performance vehicles when you are young – does represent a crucial component of accident risk: among teenagers, the risk of causing an accident increases by 20% when the vehicle has a displacement greater than 1500cc (whereas, in the case of adults, the type of vehicle plays a much more limited role). Obviously, the importance of different factors can evolve over time, along with changes in driving habits, technology and the market. For this reason, a periodic update or ‘maintenance’ of this type of measure is necessary.