Does higher Institutional Quality improve the Appropriateness of Healthcare Provision?

De Luca G., Lisi D., Martorana M., Siciliani L., 2021 – Journal of Public Economics

Healthcare spending in OECD countries represents about 9% of GDP and the majority of health expenditure is publicly financed. Health spending is expected to grow further in the next years driven by an ageing population and technological innovation, raising challenges to the sustainability of public finances. Increasing the appropriateness in healthcare provision is thus critical in making health systems sustainable.

In this critical sector, the role of the institutional framework is of paramount importance. Is the appropriateness of healthcare provision determined by different degrees of institutional quality?

Giacomo De Luca, Domenico Lisi, Marco Martorana, Luigi Siciliani provide an answer in a recently published article, Does higher Institutional Quality improve the Appropriateness of Healthcare Provision? in the Journal of Public Economics: they investigate the effect of institutional quality on the appropriateness of healthcare provision in Italian hospitals. Given the wide regional heterogeneity both in healthcare provision and institutional quality, Italy provides a particularly suitable case study.

To capture the appropriateness of healthcare provision, the authors employ a widely recognized indicator, namely cesarean section rates during childbirth for first-time mothers provided by the National Program for Outcome Assessment (Programma Nazionale Esiti, PNE). In absence of clinical reasons or complications, vaginal delivery is the recommended mode of delivery and preferred to C-section for a series of motivations, going from a higher risk of maternal mortality as well as infant morbidity. This measure is also convenient because it is vulnerable to providers’ opportunistic behaviors and thus captures eventual inefficiency of healthcare provision.

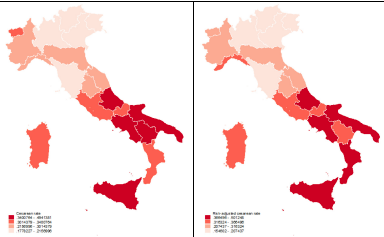

Italy exhibits large variations in C-section rates across regions that cannot be explained by sociodemographic and clinical factors. Figure 1 provides visualization on the distribution of this variable in the period 2007-2012.

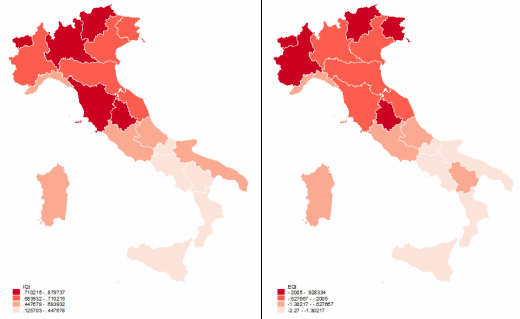

To measure institutional quality in Italian regions, the authors rely on two different indicators. The first is the Institutional Quality Index (IQI), a multidimensional quantitative indicator based on five dimensions of institutional quality: voice and accountability, government effectiveness, regulatory quality, rule of law, and control of corruption. As an alternative measure, they also employ the European Quality of Government Index (EQI), which is a perception-based multidimensional indicator. Both indicators display large differences across Italian regions, as Figure 2 clearly shows.

To identify the causal effect of institutional quality the authors rely on two historical variables capturing past cultural and political background, both available at the regional level. The first is an indicator of quality of political institutions in the period from 1600 to 1850 measured by the ‘‘Constraints on the decision making powers of chief executives” as defined by the dataset Polity IV. The second is the literacy rate in 1881. It gives a good proxy of the different cultural traits in Italian regions pre-dating the Kingdom of Italy.

The empirical strategy aims at estimating the causal effect of institutional quality on cesarean section rates, through an instrumental variable (IV) approach. Indeed, current institutions, and their quality, are largely the product of historical dynamics: therefore, the effect of past cultural traits and institutional quality are exploited as an exogenous source of variation in current institutional quality.

This study provides some strong results: institutional quality improves the appropriateness in the provision of childbirth services or, putting it differently, it plays a significant role in shaping provider incentives and in improving the efficiency of healthcare systems. A standard deviation increase in IQI leads to a reduction of about 10 percentage points in C-section rates. The results are robust to alternative indicators of institutional quality and samples. Additionally, amongst the dimensions of institutional quality, corruption and government effectiveness in the local area appear to be the most relevant in affecting the healthcare provision.

What are the mechanisms at stake? First of all, the authors suggest that a higher institutional quality maps into pro-active policies (i.e. hospitals’ payment policies) to reduce inappropriate provision. Furthermore, institutional quality positively affects not only appropriateness of care but also clinical quality: it reduces heart attack mortality rates, but it does not affect stroke mortality or mortality for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Overall, the results suggest that a worse institutional environment weakens hospitals’ incentives to select treatments that are cost-effective.

To conclude, this study puts forward some interesting insights. Paying attention to the quality of the institutional framework in which healthcare providers operate should be central in policymaking as well as long term policies enhancing their accountability. This involves expanding the scope of benchmarking across hospitals and local administrations through performance measures, and of public reporting in an accessible and user-friendly format. Finally, the analysis also suggests that in decentralized systems, the central government could play a coordinating role or introduce minimum standards to contain inappropriateness in healthcare provision.

Similar mechanisms may apply for other publicly-funded services characterized by high discretion of providers and difficulties in the measurement of performance which blur accountability (e.g., education, procurement). Indeed, whenever formal rules are missing or generic, the institutional framework is important in shaping the rules of the game and, thus, in affecting the behavior of public officials.