Economic insecurity and political preferences

Bossert W., Clark A.E., D’Ambrosio C., Lepinteur A.,2023 – Oxford Economic Papers

The rise of economic insecurity has become a major concern in recent years, influencing individual behaviours and outcomes. Economic insecurity is broadly understood as uncertainty about future economic stability. In the article “Economic insecurity and political preferences” published in Oxford Economic Papers, Walter Bossert, Andrew E. Clark, Conchita D’Ambrosio, and Anthony Lepinteur investigate whether economic insecurity affects the way in which people vote. Economic insecurity is proposed as an additional explanation of populist preferences to the cultural backlash against progressive values, such as cosmopolitanism and multiculturalism or status threat.

Despite its critical role in shaping economic, political, and social outcomes, economic insecurity remains a concept without a universally accepted definition. Prior research has addressed this insecurity in a variety of ways, such as changes in the unemployment rate, falls in per capita income, or shifts in subjective perceptions of financial stability. Given the complexity of fully accounting for all of these dimensions, the authors propose a simplified individual-level measure of economic insecurity. The new measure is constructed using a geometrically-discounted sum of income fluctuations, adhering to a set of standard axioms. Two key properties define this measure: first, loss-monotonicity, meaning that drops in economic resources increase insecurity, while rises reduce it; and second, a greater emphasis on recent experiences, so that more recent financial fluctuations have a greater influence on perceived insecurity.

The insecurity measure requires data on the changes in economic resources of the same individual over several years. This can be done using data from two well-established long-term panel surveys: the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS), for the UK, and the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), for Germany. While for the UK the time period considered in the analysis is 1991-2008, for West and East Germany it is 1985-2018 and 1992-2018, respectively.

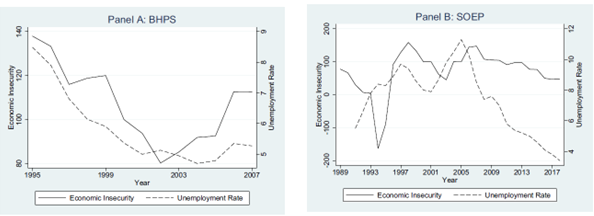

In both datasets, the authors consider annual household equivalent income (which is household income adjusted for the number of people who live in the household, reflecting the economies of scale from multiple people living together) as the main indicator of economic resources. The changes in annual household equivalent income over the past five years are then used to construct the measure of economic insecurity. As shown in Figure 1 below, the level of economic insecurity changes over time, and in tandem with unemployment.

in the UK and in Germany

Notes: The 2000 value of the insecurity index serves as base 100. The national unemployment rate is taken from the OECD Database.

Does individual economic insecurity influence political preferences? Since insecurity is linked to both unemployment and income, the study controls for both factors, along with other demographic and socioeconomic variables, in a regression analysis. This allows to isolate the effect of insecurity by comparing individuals with similar characteristics – such as sex, age, education, marital status, and labor-force status – who differ only in their economic insecurity levels. The main findings suggest that economic insecurity increases political engagement. Rather than discouraging participation, it appears to mobilize individuals, making them more likely to express support for a political party.

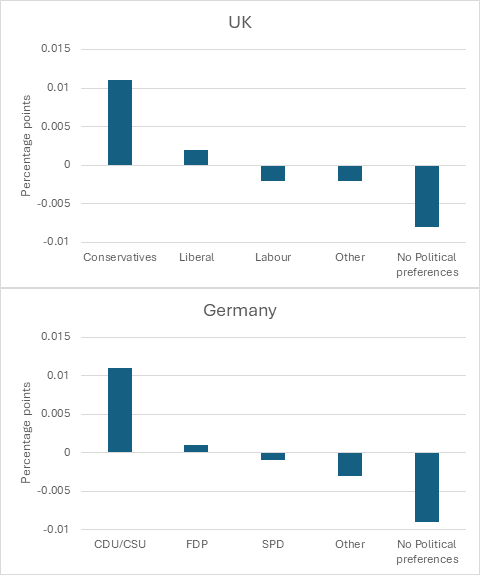

The question is then: Which political groups benefit from this higher participation? Figure 2 illustrates the impact of economic insecurity on political preferences in both countries. Multinomial logit regression analysis shows that in the UK economic insecurity is strongly associated with greater support for the Conservative Party, with no significant effect on support for Labour Party. Equally, in Germany it increases support for the CDU/CSU, with no effect on support for the SPD. These effects persist even when controlling for income, employment status, and home ownership, suggesting that economic insecurity itself – and not just financial hardship – drives these movements. The proposed measure of economic insecurity is also shown to be a better predictor of political preferences than other common indicators of insecurity that have appeared in the literature.

in the UK and in Germany

Note: These figures show the marginal effects of an increase of one standard deviation in economic insecurity on different political preferences.

If economic insecurity has contributed to Right-wing support in the UK and Germany over the past three decades, could it also be linked to the recent surge in populism? This research suggests that it is. Considering the 2016 Brexit referendum, the authors find that a one standard-deviation increase in economic insecurity is associated with a one percentage-point rise in the probability of supporting “Leave the EU”.

In addition, data from the “Understanding America Society” survey shows that higher economic insecurity increased overall voter turnout and boosted support for Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton, with no significant effect on third-party candidates.

These results are relevant. It is common to argue that insecurity reduces individual well-being; what is shown here is that it also feeds through to political outcomes. Rather than encouraging a withdrawal from politics, economic insecurity seems to encourage political activism, but of a certain kind: support for the Right.