Italy's demographic trap: Voting for childcare subsidies and fertility outcomes

Koka K., Rapallini C., 2022 – European Journal of Political Economy

Five-decades of increasing life expectancy rates and declining fertility have transformed Italy into one of the fastest aging economies among OECD countries. Italy’s fertility indeed reached its minimum in 1995, with on average only 1.19 children per woman, while a peak was registered in 2008-2010, reaching 1.44 children per woman. Then, in 2020, the average dropped again to 1.24 (but only 1.17 for women of Italian citizenship) when the pandemic exerted further negative effects on the birth rate. Indeed, partly due to the decline in conceptions starting in the first quarter 2020, the decline also continued very markedly for the first seven months of 2021 and, on the basis of the first provisional data for 2022, this drop in the birth rate is not decelerating: in the first quarter, ISTAT counts ten thousand fewer births than in the same period of the pre-pandemic period (2019-2020) with the forecast for 2022 of a new negative record of only 385 thousand births.

This trend is coupled with a strong population aging: according to recent data, residents over 65 (23.2 percent of the total) have exceeded residents under 24, who settled at 22.8 percent of the population. This demographic dynamic strongly affects also policymaking: an aging population can influence publicly provided financial support for children and families by changing the age composition of the voting electorate and voting preferences over childcare policies. If older cohorts provide less support for policies in favor of fertility, it can lead a low-fertility country into a ‘trap’ of aging and low-fertility.

In a paper entitled Italy’s demographic trap: Voting for childcare subsidies and fertility outcomes, recently published in the European Journal of Political Economy, Katerina Koka and Chiara Rapallini document the existence of this demographic trap in the Italian economy. Childcare subsidies are often used as a policy instrument to increase a country’s total fertility rate and female labor force participation. As it is typically the case, political support for policies involving tax-funded financial assistance is determined by the consequences of such policies on voters’ economic outcomes. When generational differences are explicitly considered, child benefits are expected to impact voting cohorts through both direct and indirect channels. For example, by reducing the cost of child-rearing, childcare subsidies benefit primarily younger cohorts in early stages of their working life. Older cohorts may oppose them, since they receive no direct benefits and are faced with a higher degree of income taxation. At the same time, to the extent that childcare subsides influence fertility decisions and lead to population growth, indirect effects coming through changes in prices, taxation and pension outcomes can impact all population subgroups, particularly in economies with partially funded pension systems. The net political outcome of these opposing effects involves a quantitative analysis that weighs welfare gains and losses of each generation associated with varying levels of childcare subsidies.

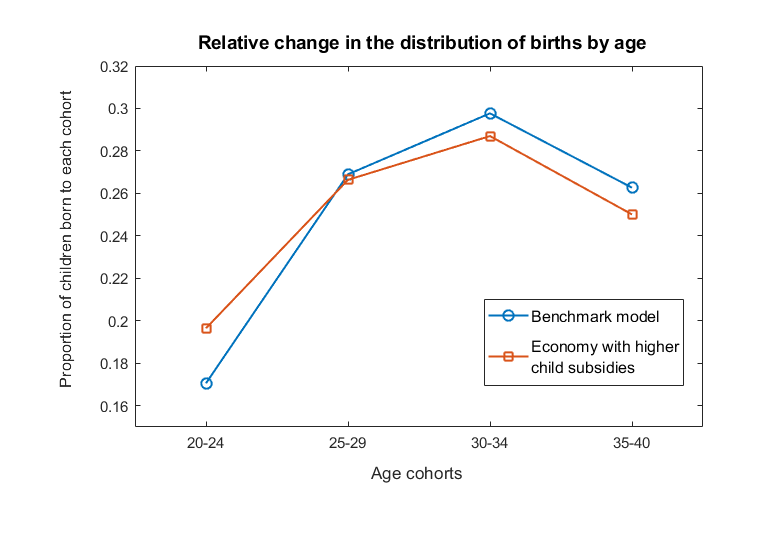

The authors’ investigation is based on a computable life-cycle model parametrized with data from Italy and calibrated to match aggregate statistics of the Italian economy as closely as possible. The analysis accounts for age-dependent fertility choices, given that increases in the mean age of women at first birth are typically associated with lower fertility rates. The model economy is used to perform counterfactual experiments that allow for the estimation of short and long run effects over a range of subsidies, income taxes and pension parameters. A probabilistic voting model with commitment is used to estimate political support and preferred policy outcomes of a voting electorate that resembles the current age composition of Italian voters. The study shows that, in the long run, increasing childcare subsidies has a positive impact on total fertility: a 10 percent increase in their level is estimated to increase the population growth rate by an average of 0.47–0.70 percentage points, depending on the financing method. Despite any negative income effects induced by higher income taxation, counterfactual economies are associated with an increase in the optimal number of children born to all cohorts and a higher total fertility rate. They are also associated with an increase in the average number of children born to younger cohorts relative to older cohorts, as Figure 1 shows.

In other words, one of the direct effects of childcare support is to increase the optimal number of offspring among younger and more fertile cohorts. Moreover, the authors give evidence that in the long-run childcare subsidies are welfare improving, whereas the size of welfare gains depends on the type of redistribution that takes place across generations. The authors show that welfare gains are larger when childcare subsidies are financed by combining an increase in labor or capital taxation with a reduction in the pension contribution rate.

Considering policy choices, the main finding of the study resides in that, regardless of the tax mix used for financing, most of the voting electorate would not support more childcare subsidies than currently in place. Said it differently, an economy with an older population – like the Italian one – does not support policies that further reduce the cost of having children and increase the total fertility rate, in spite of such policies being welfare improving in the long run. This is the reason why Italy is in a demographic trap, i.e. the majority of voters prefer to live in the low subsidy/low population growth rate-economy.

The study is aimed at increasing the awareness of the public opinion about this demographic trap. As a main policy implication, the authors highlight the importance of applying the lens of demography to debates on alternative uses of public resources. For example, a widely discussed proposal in Italy is to raise taxes on real estate. The fact that property taxes would disproportionally affect older generations is likely to be one of the reasons why the proposal lacks any substantial support. However, if the additional revenues would be used to foster fertility, long-run effects would be positive and the tax burden would be perceived as being less heavy. In addition to the long- and short-run effects highlighted through the life-cycle model adopted in the study, higher childcare subsidies would have further effects that are worth mentioning. First, in Italy – like in other low-fertility European countries – there is evidence that couples would desire two children, while the majority of them stop after the first, most commonly because of the postponement of the first child. Second, there are effects of increasing childcare subsidies that are not considered in the present study, yet, foreseeable, in terms of both financing the public budget and outcomes of the labor market. As far as the former is concerned, not only does a younger population affect public pension expenditures (as in the model adopted in the study); it also decreases expenditures of the public health system. Lastly, increasing childcare subsides is a key gender equality policy that may produce a more balanced labor force participation.