Proposing a regional gender equality index (R-GEI) with an application to Italy

Di Bella E., Leporatti L., Gandullia L., Maggino F., 2020 – Regional Studies

‘Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls’ has been identified by the United Nations (UN) as one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) ‘to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all’ by 2030. Indeed, it is now well-known that gender gaps are responsible for significant losses in economic growth, human development and, more generally, sustainable development.

Do countries present variation in gender equality also within their own boundaries? During the last 20 years, various indicators aiming at measuring gender equality have been proposed, but there are no systematic experiences of indicators tailored for a subnational analysis.

In a recent article, Proposing a regional gender equality index (R-GEI) with an application to Italy, published in Regional Studies, Enrico di Bella, Lucia Leporatti, Luca Gandullia and Filomena Maggino attempt to fill this gap. Focusing on Italy, a country that notably suffers from several territorial disparities also from this perspective, the authors first build a regional version of the gender equality index (GEI) of the European Institute on Gender Equality (EIGE): the regional-GEI (R-GEI). Next, they provide a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) to assess the dimensionality of data and explore the geographical structure of gender equality in Italy. The PCA is performed on six domain indicators: Knowledge, Power, Health, Money, Work and Time.

The final objective is to provide a set of indicators at the subnational level to describe and monitor the phenomenon at stake, to be employed as a basis for effective policy-making to achieve gender equality.

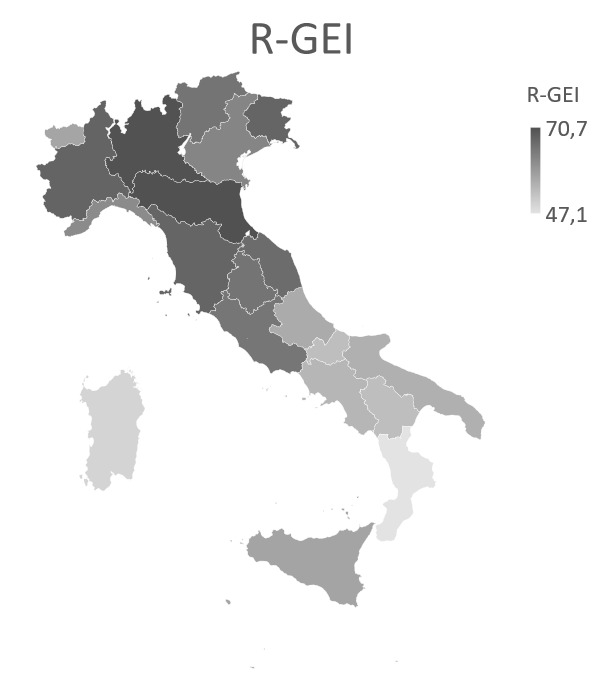

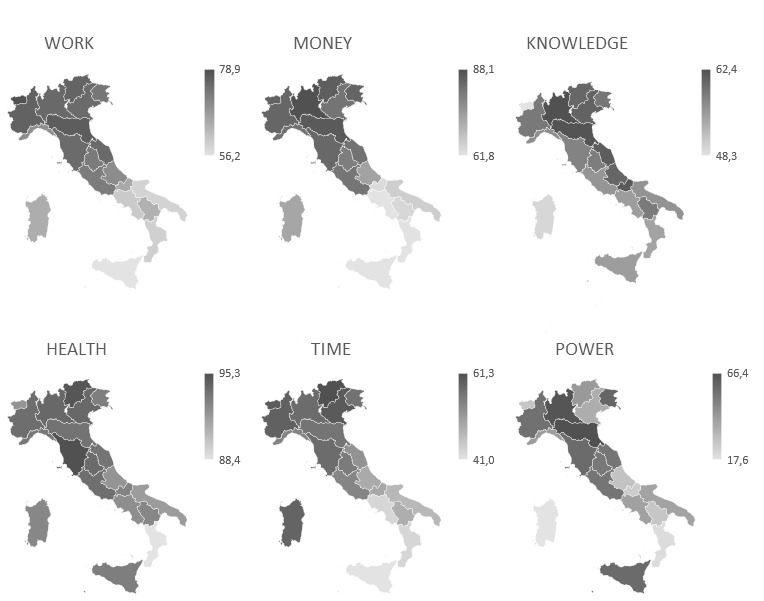

In order to highlight the territorial variability of the derived scores, Figures 1 and 2 provide the map plots of the R-GEI indicator and the six domain indicators.

The maps show that the typical North/South divide, which generally arises when socioeconomic dimensions are addressed, is also confirmed in terms of gender equality. When considering the country macro-areas (NUTS 1), northern and central regions point to a level of gender equality significantly higher than that recorded in the southern regions or in the islands. The region with the lowest level of gender equality is Calabria (46.2), whereas the most virtuous region is Lombardy (70.8), closely followed by Emilia-Romagna (70.5).

Let us now compare the R-GEI scores with the GEIs for the EU-28 countries in 2017. The two Italian regions that achieve the highest R-GEI score, Lombardy (70.85) and Emilia-Romagna (70.55), would rank 7th and 8th in Europe, just below France (72.6) and the UK (71.5) and above Belgium (70.5). The two regions with the lowest score, Calabria (46.29) and Sardinia (48.69), are well below Cyprus (51.9) and Greece (51.2), the two countries with the lowest GEIs.

Gender gaps between men and women are particularly evident in the domain of Power, with Sardinia displaying a score of 16.2 against the highest value of 66.2 of Lombardy. The domains in which regional disparities are more relevant are those of Power, Money, Time and Work. On the contrary, the domains of Health and Knowledge show significantly lower variation.

Two important remarks arise from the study. First, the Italian national score of gender equality is unsuitable for fully capturing the severe regional disparities within the country. Realistically, this can be assumed to be true for most European countries, particularly those characterised by intermediate or low national gender equality indicator scores.

Second, most of the differences in the Italian North/South gender gap relate to the economic sphere. It is noteworthy that the domain of labour market participation is partially related to that of Time: indeed, still today women tend to bear a heavier burden in terms of family keep and care. This is partially a consequence of cultural, traditional and religious values, and this aspect is probably able to explain the great regional disparities in this perspective.

These results are potentially very useful for policymakers at identifying the most relevant areas of policy intervention as well as the specific measures to implement. In the last decades in Italy, after a substantial process of decentralization of decisional powers towards subnational governments, many public policies have focused on achieving gender equity and have been assigned to regional governments (e.g., the implementation of family-friendly measures to improve female participation in the labour market).

At the same time, beyond equal pay legislation and the promotion of equal opportunities adopted at the central level, according to Article 119 of the Constitution, the central government may take differentiated intervention policies on a regional basis, explicitly aimed at removing economic and social imbalances (e.g., paid leaves from work), especially in the private sector where gender gaps in wages are more pronounced.

As clearly highlighted by this study, nowadays, gender gaps in both wages and participation in the labour market is a very relevant issue in the southern area of the country. Reducing such gaps should become an absolute priority of policy-making. Moreover, with regards to work-family reconciliation policies, public kindergartens are ruled by local governments, and there exist wide disparities in terms of availability and supply across regions. According to ISTAT (2019), in the North-East of Italy, the number of public kindergartens services is 18.3 for 100 infants under two years of age, whereas this is only 5.6 in southern Italy. It is evident that improving the availability of educational services for infants in these regions may be crucial for reducing territorial differences in female participation in the labour force.

To conclude, a regionalized approach to gender equality is necessary to set priorities and target regional policy actions. The R-GEI may become a useful instrument for both national and local governments to target resources towards those regions more in need for a gender gap reduction, and direct local policy actions towards interventions that are better tailored to the weaknesses of each region.