R&D and market size: Who benefits from orphan drug legislation?

Gamba S., Magazzini L., Pertile P., 2021 – Journal of Health Economics

It is now widely acknowledged that the development of new health technologies is among the key determinants of the upward trend in life expectancy that most countries have experienced. Although the overall picture looks reassuring, we cannot ignore that not all patients have benefited in the same way of such developments. Technical aspects of the discovery process may explain the lack of development in selected clinical areas. However, economic reasons may also play a central role, as is the case for rare diseases, for which the small size of the potential market means that the incentive for the private industry to invest in these clinical areas is often too scarce. Even though each single rare disease usually affects very few people, currently more than 7,000 orphan diseases are described in the literature, and it is estimated that 27 to 36 million EU residents suffer from an orphan disease. What is most striking is that a treatment with a specific indication is available for less than 10% of known rare diseases. This makes rare diseases a huge and largely unresolved public health issue.

Awareness of this issue led several countries to introduce special legislation, starting from the approval of the Orphan Drug Act (ODA) in 1983 in the US. In the following years, other countries took similar initiatives, including Japan in 1993 and the European Union in 2000. The toolkit is similar, although not perfectly overlapped, across geographic areas, and includes both pull and push incentives. Pull incentives are market related incentives, such as market exclusivity, a particularly strong form of market protection. In turn, push incentives reward the R&D process (e.g., through tax credits or other forms of subsidy), irrespective of the ability to reach the market. Medicines eligible to access these incentives are those that receive the Orphan Drug Designation (ODD) from the competent regulatory authority.

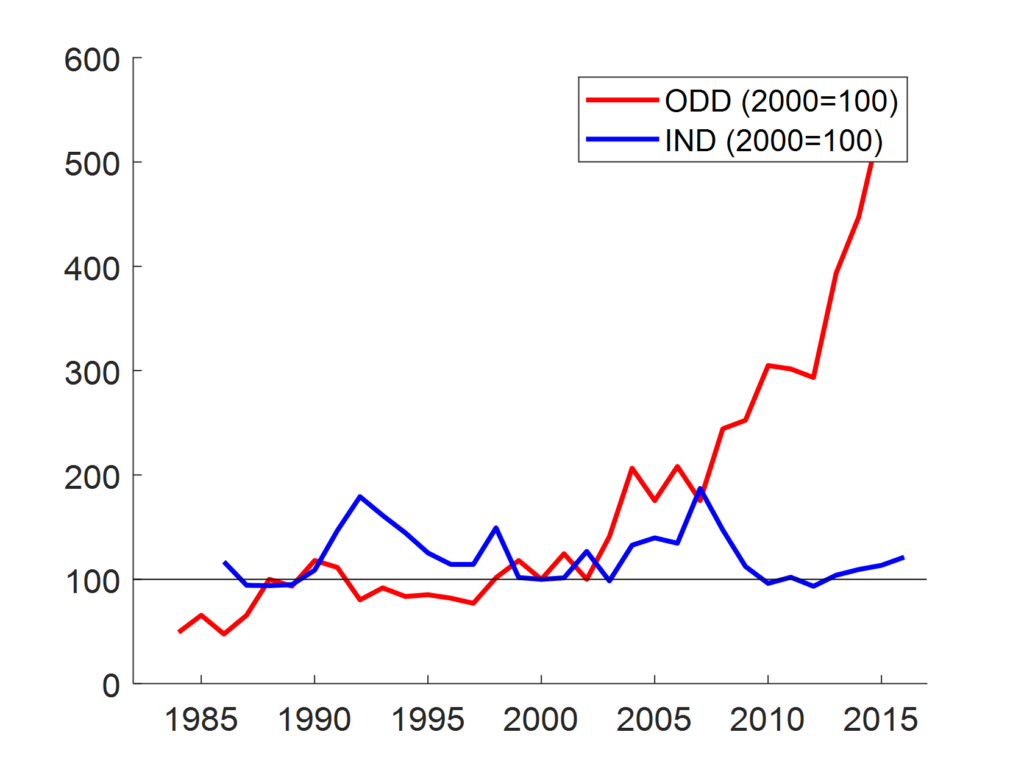

Is this special legislation effective? If the question is whether it contributed to closing the overall R&D gap between orphan and non-orphan diseases, then the answer provided by the literature is definitely yes. Based on data from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Figure 1 compares changes over time in a measure of R&D intensity typical of rare diseases (Orphan Drug Designations) with a more general one (Investigational New Drugs). The figure shows that the growth was much greater for the former class, especially since 2000.

new drugs (IND) applications (blue line);

However, starting from this evidence, it is natural to ask one further, perhaps more interesting, question: who benefits from orphan drug legislation?

In a recent article, “R&D and market size: Who benefits from orphan drug legislation?“, published in the Journal of Health Economics, Simona Gamba, Laura Magazzini, and Paolo Pertile investigate this issue and study how the impact of the incentives changes according to the prevalence of the disease. In fact, whereas some orphan diseases affect several hundred thousand individuals worldwide, others record very few cases. Hence, although the size of the market for an orphan disease is typically small, in some cases it is much smaller than in others.

In their analysis, the authors first elaborate a theoretical model, in which manufacturers make two decisions: first, they decide whether or not to invest in R&D targeting a certain disease, based on a comparison of expected revenues and costs; if the answer to this question is positive, then they decide how much to invest. It is well known that R&D processes are highly risky. However, the probability of success is greater the larger the amount invested in R&D is. As expected, both pull and push incentives provide a positive contribution to investment. However, they work in different ways. Pull incentives tend to widen the gap in terms of investment between less rare and rarer diseases more than push incentives do.

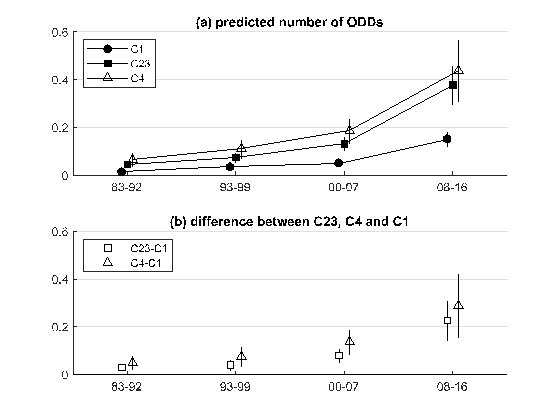

Then, the authors empirically test these theoretical conclusions by combining two separate sources of data: the Orphanet database containing information on rare diseases and FDA data on ODDs. Figure 2 plots the predicted number of ODDs for three classes of diseases based on their prevalence: ultra-rare (C1: <1/1,000,000), intermediate (C23: 1/1,000,000-9/100,000) and not so rare (C4: 1-5/10,000). Predictions are based on a Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial model that combines the decision on whether or not to invest and the investment intensity (conditional on positive investment).

The figure shows that over time the gap in favour of less rare diseases widened substantially. In particular, the difference between the predicted number of orphan designations per year for a disease in the highest and the lowest class of prevalence was 5.6 times larger after 2008 than in the period 1983-1992. Based on the theoretical analysis proposed by the authors, the type of incentive deployed is likely to have contributed to this dynamic. This is particularly true for the European legislation introduced in 2000, where the weight of pull relative to push incentives is greater than in other geographic areas.

The results of this research are relevant in terms of policy implications, since a process of reform of the pharmaceutical regulation, including the orphan legislation, is currently ongoing in Europe. How could the system of incentives be revised to reduce the number of diseases for which there exists no therapeutic option? The present analysis suggests that strengthening push incentives, which are particularly weak under the current EU legislation, might help. However, more radical changes could be needed to achieve the objective. The current system is grounded on a basic definition of orphan disease referring to a simple indicator of prevalence (less than 5 in 10,000). The incentive system is then the same for all diseases classified as orphan. If providing some therapeutic option to patients with very rare diseases is a priority, then incentives should be tailored to the particular disease prevalence within the general class of orphan diseases. Alternatively, stronger forms of incentives could be conceived for diseases with no existing therapeutic option, or for those with a particularly large burden of disease. The disconnection between corporate R&D choices and public health priorities might also be solved by the creation of a public infrastructure, focusing on areas of research that are underinvested under the current business model.

For further details on the process of reform of pharmaceutical regulation, see: