Women’s voice on redistribution: from gender equality to equalizing taxation

Bozzano M., Profeta P., Puglisi R., Scabrosetti S., 2024 – European Journal of Political Economy

How does gender equality shape redistribution? Redistribution is a core objective of public policy, which largely takes place through a progressive taxation. In representative democracies, policies reflect (or should reflect) citizens’ preferences, which differ across various dimensions, including gender. However, both political institutions and preferences often have strong historical inertia, i.e., history could matter.

In a paper entitled “Women’s voice on redistribution: From gender equality to equalizing taxation”, recently published in the European Journal of Political Economy, Monica Bozzano, Paola Profeta, Riccardo Puglisi, and Simona Scabrosetti explore the connection between gender equality – and its historical roots– and redistribution.

The authors first analyze the relationship between the historical roots of gender equality and the level of redistribution through taxation at the cross-country level. This aggregate analysis is based on 143 countries during the 2000–2016 period. To capture the equalizing effect of the tax system, the dependent variable is the ratio of direct taxes over indirect taxes, computed using the ICTD/UNU-WIDER Government Revenue Dataset. Direct taxes are typically, if not intrinsically, progressive, because of the equalizing effects of tax brackets, fixed deductions and allowances, whereas indirect taxes are generally regressive. Since the equalization of disposable income is achieved through greater progressivity of the tax system, direct taxation should be preferred to indirect taxes to raise revenue and achieve redistribution. As a result, a higher level of redistribution is more likely to occur caeteris paribus when the balance between direct and indirect tax revenue tilts towards the former. Therefore, the higher the ratio, the higher the equalizing effect of taxation on income.

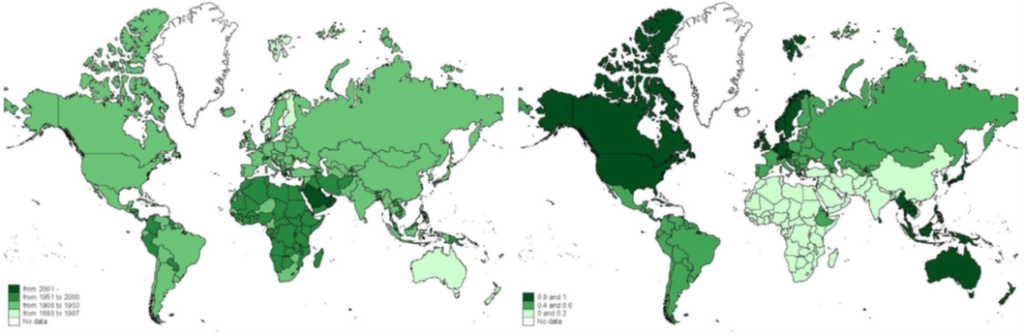

Historical roots of gender equality are captured by two different variables. The first is the timing of women’s enfranchisement, and the second is the degree of feminism in historical family structures, categorized by the authors based on the work of the sociologist Emmanuel Todd. Figure 1 displays the geographical distribution of the two variables.

Note: The darker the shade for a country, the more recent enfranchisement on the left or the stronger the degree of feminism in family structure on the right.

Controlling for a broad set of economic, demographic, and political factors in a more parsimonious specification, as well as for historical, cultural, and geographic controls in a larger one, the estimates reveal a striking pattern: in countries with earlier women’s enfranchisement and/or where women historically played a more relevant role within the family, the share of direct taxes (over indirect taxes or total tax revenue) is significantly higher than in countries with a later enfranchisement and with historical gender inequality within the family.

To complement these cross-country findings, in a second part of the study, the authors provide additional evidence at the individual level to further explore redistributive preferences. For this analysis, they use the European Social Survey (ESS), a biennial, repeated cross-section dataset covering attitudes and behaviors across 34 European countries from 2002 to 2016.

The dependent variable measures the agreement with the statement: “The government should reduce differences in income level’’. The variable is recoded so that the higher the value, the more favorable to redistribution the individual is.

Current gender equality is measured by the Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI) from World Economic Forum. This index measures gender-based disparities in outcomes in four dimensions: political empowerment, economic participation, education, and health. The GGGI ranges from 0 to 1, higher values indicating greater gender equality.

The authors test two hypotheses based on two, not mutually exclusive, mechanisms. According to the former, in more gender-equal environments both women and men are more favorable to redistribution, which of course implies a positive correlation between gender equality and average redistributive preferences. This is because equality in the gender domain may ‘‘translate into’’ a drive for equality in the economic domain, thereby similarly influencing the preferences of both women and men. According to the latter, gender equality is differentially associated with the redistributive preferences of men and women, thus implying a larger or smaller gender gap in those preferences.

The results support the latter mechanism, while it rejects the former one.

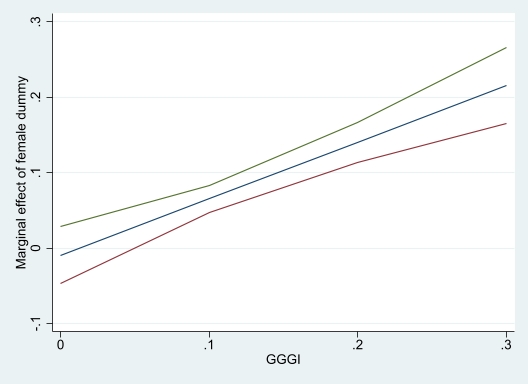

Figure 2 offers a graphical visualization of the partial correlation of the female dummy with pro-redistribution preferences as a function of aggregate gender equality, computed from the focal regression in which preferences for redistribution are a function of a set of individual socio-economic characteristics, i.e., income, education, age, marital status, household characteristics, religiosity, and political ideology, as well as the country’s per capita GDP.

The partial correlation of interest is almost always positive and increasing with the GGGI, i.e., in more gender-equal environments the (positive) gender gap in redistributive preferences is significantly larger, whereas their average level does not vary. This difference is statistically not significant in environments with the lowest level of gender equality. Furthermore, in a set of estimates focussed on the four components of the GGGI, the authors highlight that the one eventually driving this result is – not surprisingly – the equality of women and men within the political sphere: in other words, women are significantly more favorable to redistribution vis-à-vis men in politically more equal environments.

The blue line represents the estimated partial correlation of the female dummy in a regression for redistributive preferences as a function of GGGI. The red and green lines identify the upper and the lower bounds of the 95% confidence intervals.

This finding is further strengthened by integrating cross-country and individual-level data using an Instrumental Variable approach, where the timing of women’s enfranchisement and the historical role of women within the family serve as instruments for gender equality – and for gender equality in the political domain – nowadays.

To summarize, the authors show that in countries with earlier women’s enfranchisement and/or where women historically played a more relevant role within the family, the level of redistribution through taxation is higher than in countries with a later enfranchisement and with historical gender inequality within the family.

At the individual level, gender-equal environments amplify differences in redistributive preferences, where the ‘‘action’’ comes from women being systematically more favorable to redistribution, and with no significant changes for men. In line with the ‘‘resource hypothesis’’, dubbed by Falk and Hermle (Science, 2018), the present evidence argues that women are inherently inclined to prefer redistribution more than men – possibly because of a (social) insurance/risk aversion motive – and that in more gender-equal societies this gender-based difference in redistributive preferences is ‘‘socially’’ allowed to emerge. Notably, the larger gender-based difference in redistributive preferences in more gender-equal environments is driven by female political empowerment.

To the extent that income redistribution is normatively considered as a fundamental task for the government intervention in a market economy, these findings emphasize the opportunity to promote gender equality overall and in the political domain, in order to more effectively pursue the redistributive goal. From a predictive point of view, it would be interesting to explore whether in the long run the stronger pro-redistribution ‘‘voice’’ of women in more gender-equal environments would translate into a faster reduction of gender differences in income and wealth.