Working from home and income inequality: risks of a ‘new normal’ with COVID-19

Bonacini L., Gallo G., Scicchitano S., 2021 – Journal of Population Economics, awarded with the Kuznets Prize 2022

To limit the number of deaths and hospitalisations due to the novel coronavirus, most governments decided to suspend many economic activities and restrict people’s freedom of mobility. In this context, the opportunity to work from home (hereinafter called WFH) became of great importance. First, WFH allows employees to continue working and thus receiving wages and employers to keep producing services and revenues. Moreover, it limits infection spread risk and pandemic recessive impacts. Due to uncertainty about the duration of the health emergency and future contagion waves, the role of WFH in the labour market is further emphasized by the fact that it might become a ‘new normal’ way of working in many economic sectors, possibly resulting in structural effects on the labour market worldwide. Because of the WFH sudden prominence and growth, several studies recently investigated this phenomenon, especially with the objective of identifying the number of jobs that can be done remotely. However, the literature initially neglected potential effects of WFH on wage distribution and on income inequality in general.

In a recent paper, Working from home and income inequality: risks of a ‘new normal’ with COVID-19, published in the Journal of Population Economics, Bonacini, Gallo and Scicchitano fill this gap exploring how a future increase in WFH would be related to changes in labour income levels and inequality. Specifically, they analyse to what extent an increase in the number of employees who have the opportunity to WFH (or at least an increase in the likelihood their professions can be performed from home) would influence the wage distribution, under the hypothesis that this WFH feasibility shift is long lasting.

The authors focus on Italy as an interesting case study because it has been the first Western country to adopt lockdown measures. Moreover, Italy was the European country with the lowest share of teleworkers before the pandemic. Their analysis relies on a uniquely detailed dataset relying on the merge of two sample surveys: the Survey on Labour Participation and Unemployment (INAPP-PLUS) for the year 2018, which contains information on incomes, skills, education level, and employment conditions of approximately 45,000 working-age Italians; and the Italian Survey of Professions (ICP) for the year 2013, which provides detailed information on the task-content of occupations. The ICP survey represents the Italian equivalent of the notorious US O*NET database. The authors define the WFH feasibility by means of an index, recently available in the literature, and divide Italian employees in two categories (low level and high level of WFH feasibility) using the sample median value of this index as threshold.

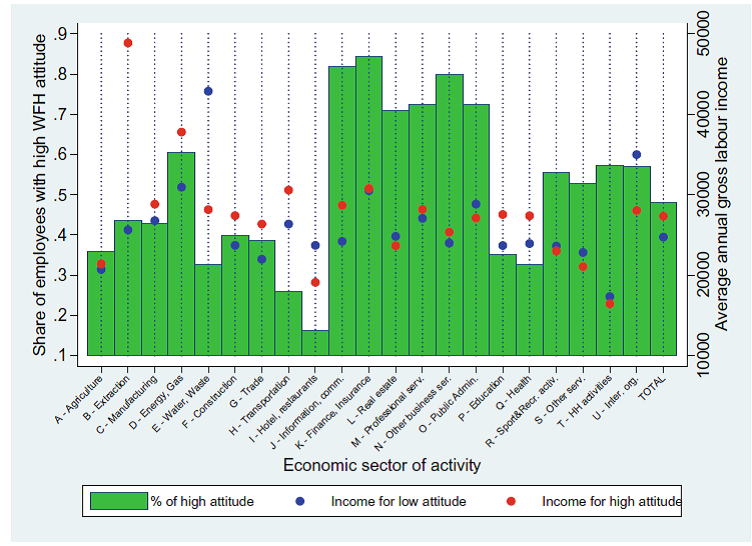

First of all, the authors show that employees with high WFH feasibility levels are more often female, older, highly educated, and among those living in metropolitan areas. Economic sectors being characterized by greater shares of employees with high WFH feasibility are: Finance and Insurance, Information and Communications, Other Business Services (e.g., car renting, travel agencies, employment agencies) and Public Administration (Figure 1). Figure 1 also highlights that the employees with high level of WFH feasibility receive on average a greater annual labour income than the others (€27,300 vs €24,700), and that happens in most of sectors.

Figure 1. Incidence of high WFH feasibility and average labour income by activity sector

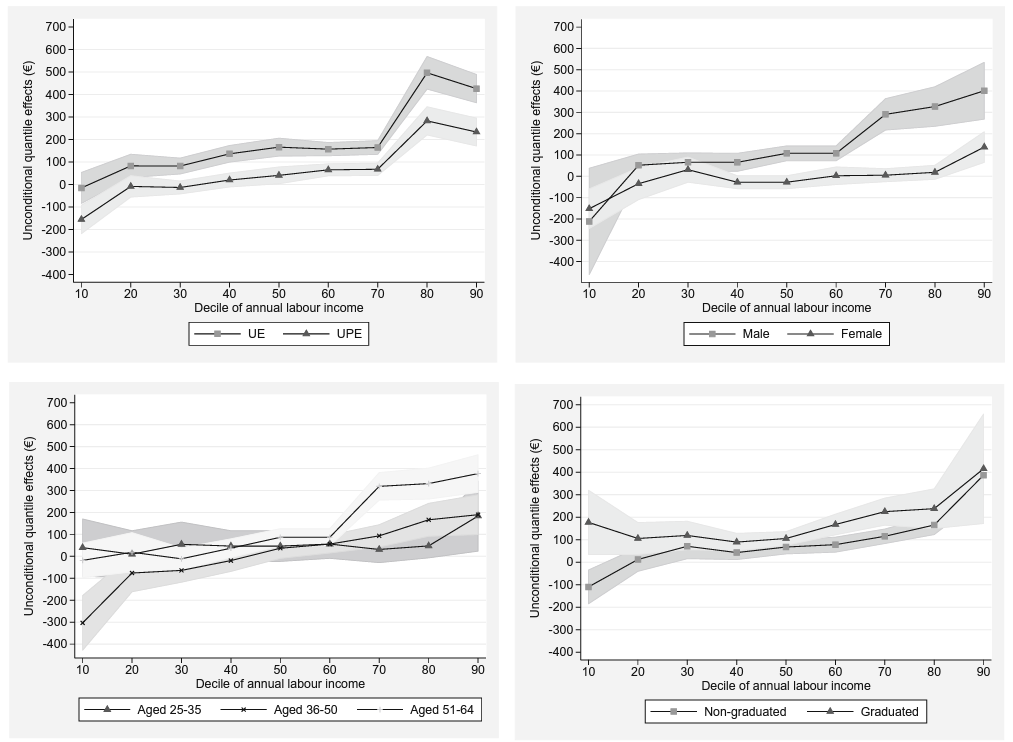

The econometric analysis is made through an unconditional quantile regression method which allows to estimate the influence of marginal changes on an outcome variable distribution. The authors’ results show that an increase in WFH feasibility would be associated with an increase in the average labour income, but this potential benefit would not be equally distributed among employees. Specifically, disaggregating by employees’ characteristics, an increase in WFH feasibility would mainly favour male, older, high-educated, and high-paid employees (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Unconditional effects of a positive shift in the WFH feasibility along labour income distribution (Confidence Intervals at 90% level)

This “forced innovation” thus risks to exacerbate pre-existing inequalities in the labour market. In this respect, while during the current emergency, policies aimed at alleviating inequality in the short run (e.g. income support measures for the most vulnerable), should be implemented, long-term interventions are even more necessary in order to prevent future rise of inequalities in the labour market.

These long-term policies go in three interrelated directions:

- The necessary massive reorganisation of work, particularly in the field of reengineering of production processes based on new digital technologies and on the possibility offered in terms of WFH requires new and more widespread skills.

- Researchers need to promote through adequate economic and cultural incentives, non-compulsory education for youth coming from poorer households. This would include training courses, which would play an important role in reducing future unequal distribution of benefits related to an increase in WFH opportunities, by increasing human capital and favouring its complementarities with technology.

This study highlights that, while most of the increase in WFH will concern women, the wage premium would be borne by male employees. In this perspective, a possible, non-exhaustive solution could be offered by policies aimed at improving work–family reconciliation, that continues to be shouldered more significantly by women. In particular, the authors stress the importance of an improving of public childcare and financial support to households with children.